The Write Stuff

by Jim Waltzer

New Jersey Lifestyle Magazine 2008

Before James Rahn parlayed an Ivy League education into a unique writers’ workshop, he had to figure out how to graduate from high school.

Before James Rahn parlayed an Ivy League education into a unique writers’ workshop, he had to figure out how to graduate from high school.

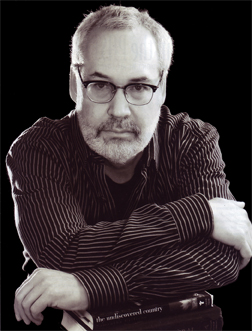

Those who appreciate fresh language and rich storytelling have gathered in the auditorium of the Free Library of Philadelphia to hear Diane McKinney Whetstone read from her latest work. But before the novelist takes the stage, another figure stands at the podium. The glasses are wire-rim and the gray hair is threatening to go white, but this is no garden-variety professor. There is both respect and vigor in his stance, his celebration of the evening’s featured author. His words are bite-size but full-bodied. McKinney-Whetstone’s dialogue, he says, is often “like breath.” He cites her “great voice” as a writer.

It took Atlantic City native James Rahn awhile to find his own voice, but now that he has, it’s coming through static-free. Just ask the member―and former members like McKinney-Whetstone―of Rittenhouse Writers’ Group, the center-city Philadelphia fiction workshop he founded twenty years ago and still leads. If life is tough, fiction is tougher, but the Rahn road map leaves few stranded.

“James is very good at helping the writer to see where the energy is,” says Cherry Hill resident Stefanie Levine Cohen, a nonstop participant since 2002.

Energy was never the problem for James Rahn. Growing up in the lower Chelsea section of Atlantic City in the 1960s, a time when the town’s prospects were dimming, he bopped from schoolyard to sub shop in his working-class neighborhood. Soon enough he exchanged the classroom for the street world, leaving Atlantic City High School midway through his junior year.

That’s right, this future writing coach of best-selling novelists was a high school dropout before his 16th birthday. He was in good, or rather, bad, company.

“A lot of my friends had quit,” says Rahn. “I got into mischief as a youth. It was a bit of a self-destructive phase.”

It was not the family blueprint. His maternal grandfather had been Chief of Obstetrics at Atlantic City Hospital, and his father, a dentist who, according to family lore, had been the elevator boy at the Ritz-Carlton and earned enough money in tips from town boss “Nucky” Johnson to pay for dental school. Both men were gone, however, by the time Rahn (the youngest, by 11 years, of four siblings) became an unmoored adolescent. He brought home report cards with straight F’s. “I didn’t care,” he says simply.

His crowd sampled the wider world, which included such exotic Atlantic City locales as Ducktown and the Inlet. There were dares followed by fights followed by more dares, a dynamic that tends to grab him when it appears in the writing he now evaluates. “It stemmed from economic conditions in Atlantic City [at the time],” Rahn says. “We used to think that Margate people were the rich people…During the summer, there was friction between Philly kids and the locals.”

Rahn drifted and duked it out and worked some carpentry jobs before smartening up. He knew he could pass the GED exam and did so. That was his entry in 1972 to nascent Stockton State College, which was then holding classes at Atlantic City’s old Mayflower Hotel. His appearance startled students who knew him from Atlantic City High and had earned their diplomas the old-fashioned way. “They asked me, ‘what’re you doing here?’” says Rahn. “I had to make up what I missed in high school from not going to high school.”

Independent studies courses at Stockton matched his mindset and stoked his learning. Professors responded to his drive, and discussed the likes of Poe and Faulkner with him. After two years, Rahn was ready for a larger forum and applied to the University of Pennsylvania, which admitted him in the fall of 1974. He majored in English at Penn and graduated with honors two years later.

For the seashore dropout, it had been quite a turnaround. “It was a shock,” he says.

Wanderlust, however, still ruled James Rahn. He took a job in New York with a trade-show supplier, donned a suit, and supervised the setup crew. The he hit the road in earnest: south to Tennessee, west to California, overseas to France and Ireland, writing at each stop and earning his keep with manual labor. “It was an odyssey of self-discovery,” he says, in a writerly turn.

Nice work if you can get it.

Back stateside in Miami Beach, the peripatetic Rahn read a Vanity Fair article about flamboyant writer-editor Gordon Lish’s foray into teaching fiction workshops. Intrigued, he soon returned to Atlantic City to plan his next move. He’d made and relinquished a small bundle trading casino stocks and, subsequently, almost landed a job as a stockbroker (if you can’t beat ‘em…). Instead, he applied to the writing program at Columbia University’s School of the Arts. If it were fiction, he’d have demanded smoother transitions.

When Columbia accepted Rahn, it was back to New York for a two-year masters program a full 10 years after he’d graduated from Penn. He never did catch up with the legendary Lish, who taught at Columbia during that period, but did take multiple writing workshops and developed a plot line for his future. “I felt like my life was coalescing,” he says. He had met his future wife, an Atlantic City native. And he had met his métier as well. “A few guys from class started [fiction writing] workshops in New York. They explained the elements of putting them together. There’s intuition involved, luck, some analytical ability…”

Armed with such building blocks and a graduate degree from Columbia, Rahn launched his own workshop in the fall of 1988 in Philadelphia, renting space at the artsy Ethical Society building on Rittenhouse Square and hustling flyers around town. He called his fledgling enterprise Rittenhouse Writers’ Group, attracted a band of intrepid souls for opening night, and admittedly battled flop-sweat after running out of material within five minutes.

Things have since improved. As the group celebrates two decades of word wars, the roster changes but familiar faces persist. Hainesport resident Lisa Paparone, an accountant and financial planner by day, has been attending evening workshop sessions for 15 years.

“You don’t get many ‘numbers-type’ people in the workshop,” says Paparone, who sees her pursuit as a way to keep in touch with her creative side. “I get a real charge out of writing a story and getting a good response.”

Favorable reactions are not unusual across the Rittenhouse Writers’ Group table, but the atmosphere is thick with the egos and raw nerves common to the breed. “It took me a workshop or two to develop enough of a shell to take criticism,” says Levine Cohen. “Your heart is on the page.”

Fortunately, workshop leader-cardiologist Rahn is on hand to keep things civilized even as he spots the cracks in a story’s foundation. His prescription is always to work the writing, fully imagine the scenes, find the center. His insights are both general and specific, his manner direct but sensitive to individual temperaments and his own imperfectness. He cares about the material and the writer.

When the crucible concludes, the gang goes out for burgers and beer.

“That’s so James,” says Paparone. “But he’s kind of secretive about his life. In a way, that helps the workshop.”

The workshop’s fearless leader may not broadcast it, but he’s learned a thing or two about himself. Self-revelation can be a powerful tool for a writer, or anybody, for that matter. Rahn, who’s published short stories and magazine articles, has been studying at the Psychoanalytic Center of Philadelphia, a non-profit that explores human behavior. “It’s the best education I’ve ever had,” says the Penn-Columbia grad. Instead of schoolyard to sub shop, his axis now links the Ethical Society on Rittenhouse Square with PCOP’s home in Fairmount Park’s historic Rockland Mansion.

That’s moving up in the world.

“I used to feel unlucky, but now I feel lucky,” says Rahn. “I enjoy surprises.”

Which fiction writers try to create, and their instructors, if they’re any good, always encourage.